Ron Cooper Finds Mezcal, Or Rather, It Finds Him

I’m sitting at a bar in the heart of Taos Plaza in the middle of the day with Artist/Mezcal négociant (a French term for an importer who’s intimately involved in the procuring of wine, yet puts his own inimitable mark on said product) Ron Cooper as a John Prine song plays in the background to set the mood.

It’s dark and quiet inside as we hunker down on the pine and talk about those things men do in bars. Cooper’s a thirty-year resident of Taos, a Southern California transplant that came out during the days of New Buffalo looking to push the envelope of the emerging paradigm of peace, love, and community. A vivacious septuagenarian, he wears his still-black and occasionally laced-with-silver hair in a samurai top-knot, and always seems to be wearing the same Mexican peasant shirt of off-white.

He’s in the middle of spinning one of his engaging yarns, locking his intense coal-black eyes into mine and leaning in closer as the tale crescendos when our food arrives. He doesn’t skip a beat as he hands me a share plate and chucks a few pommes frites in his mouth, adding, “If I don’t know you personally, I’m probably not going to listen to what you’ve got to say,” he matter-of-factly states in regard to the unsolicited advice he often gets from big-time spirits-industry professionals who’ve come sniffing around of late, as his multi-decade project Del Maguey Mezcal shoots into the stratosphere, garnering several James Beard Award nominations along the way and most recently a Best New Product award from the non-profit, industry darling Tales of the Cocktail Awards for his Ibérico Mezcal.

Held annually in New Orleans, Tales of the Cocktail is the world’s premier spirits festival that brings together an international cast of the brightest spirits professionals who engage in seminars and intense competitions for several days — a sort of “Fight Club” of the best from the cocktail world.

You’re expected to show up and deliver at Tales, as top-tier career bartenders and spirits professionals have no mercy in their relentless approach to determining what they know will work in real time out in the real world.

The Tales victory was particularly sweet for Cooper, due to the fact that for seventeen years Del Maguey scratched and clawed to stay alive, often doing so merely by the occasional profits Cooper reaps from selling a piece of his art.

However, to Cooper, there’s no differentiation between studio art and the art of mezcal production.

When asked by a writer from Tequila Aficionado, “Do you consider mezcal an art form?” Cooper succinctly replied,” A work of art is successful to me if in the act of experiencing it one is transformed in some way. A good mezcal is certainly transformational, so it fits my criteria for art.”

Cooper’s philosophy about art and life were formed in part by the Dadaist movement instigated by Marcel Duchamp in 1913. Duchamp and Dadaism begged the important questions, “What is art? Something we’ve worked hard over? Something ‘elevated’? Where do these evaluations come from? Why do we believe in them or invest them with credibility?”

European transplants like Duchamp who relocated to the West Coast were also largely influenced by the spirit of Zen that permeated California culture – which, unlike the East coast has more to do with Asia than Europe.

Cooper is a child of the conjunction of European re-invention and the influence of Zen philosophy. The infinite, cerulean-blue skies of his Pacific childhood providing the inspiration to deconstruct and question the dogmas of post-WWII reality and informing his instincts in order to create in a boundless way that placed him at the cutting-edge of the Los Angeles art scene of the 60’s and 70’s.

His raw visual materials and subconscious matter are a sort of “greatest hits” of his coming-of-age in California culture; surfboards and hot rods, neon lights, Buddhist iconography and Mexican motifs all permeate the man and his objects.

Del Maguey represents more to him than just a business, a beverage, or a passion. The twelve Oaxacan villages he sources his mezcal from are spiritual homes for him and he was inculcated into their particular pre-Columbian rituals back in the 70’s when Del Maguey and mezcal became his true path in that Carlos Casteñeda Don Juan way; when a man must choose a heart path at particular junctures in his life, getting out of it what he puts in.

Undoubtedly, there was many a dark night of the soul for Cooper in the ensuing decades when Del Maguey was misunderstood and underrepresented. Until recently, most consumers were completely unaware that Tequila is not a spirit in and of itself, but merely a region where mezcal is produced. Mezcal production happens throughout Mexico, and Oaxaca historically is one of the oldest and more renowned producers, with the harvesting and production of the sacred maguey happening in the same way since Aztec and pre-Aztec times.

The Zapotec, Mixtec, and Mixe producers Cooper works with go about their business in the manner their forefathers taught them. The maguey plant is anthropomorphized and spoken to in a sacred manner, from the heart. It is asked permission to be harvested and production is never excessive or for the sake of mere profit, but more often than not used solely for celebratory rituals in the village and Cooper established set limits for export in conjunction with the villages, taking only what are considered to be acceptable to the plant and environment.

In the Footsteps of Those Who’ve Walked Before

Although it may seem improbable Oaxacan mezcal and New Mexico be connected in any meaningful way, the fact is the El Camino Real (running from Mexico City to Santa Fe) has historically shipped mezcal from Mexico since at least the nineteenth century, with the first mention of the transport happening in the town of Tequila’s tax record of 1873, where there’s an entry for a shipment of “vino de mezcal de la region de tequila” sent to Santa Fe.

What’s also telling about the entry is the terminology used to describe the product. “Vino de mezcal,” or “mezcal wine,” is the original term applied by Spaniards upon their colonizing of Mexico and used primarily due to the advanced production techniques they witnessed the indigenous Indians using and the superior product it produced, which must have made the imported Spanish table wine imported across the Atlantic in crude earthenware pale in comparison.

Cooper’s kept the vino de mezcal terminology alive with a series of small-batch, hand-picked vinos he refers to as “folk art you can drink.” The collection all seem to be steeped in folklore and each have uncanny, serendipitous circumstances associated with their production.

For example, the San Jose Rio Minas 100% maguey espadin, produced in the tiny village of San Jose Rio Minas was merely a rumor Cooper was intent on investigating, eventually seeking it out one day via car, yet after several hours journey on undeveloped pot-holed country roads, the place seemed unapproachable and he resigned himself to having to pass on finding the village, when he suddenly came across a group of deer hunters on the road who’d been travelling quite some time on foot. Cooper asked them if they were familiar with the mezcal of Rio Minas, and their spokesman Don Roberto laughed heartily while motioning to one of his comrades to hand him what turned out to be a half-liter plastic water bottle with said mezcal its contents. They passed the bottle to Cooper for his first taste, and the rest is history.

The Arroqueno — Santa Catarina Minas 100% maguey Arroqueno is procured from semi-wild maguey and is dedicated to Biologist and explorer Thor Heyerdahl of Kon Tiki fame and produced in the ancient way where the magueys are roasted in a conical pit over hot coals, buried with earth for three days, fermented with nothing but airborne microbes for thirty days, then twice-distilled very slowly in an antiquated clay still with bamboo tubing. A mere 360 bottles were produced, and the resulting mezcal exhibits notes of lush cantaloupe and a hint of baking chocolate against a fresh, savory finish that stretches out on the palate.

The Single Village Mezcals Cooper and Del Maguey came to prominence on are the result of his heart path, whose main currency is the face-to-face relationship. His ability to procure these organic, single-village, small-batch wonders shouldn’t be overlooked, as they are the heart and soul of the rituals and spiritual life of the arcane villages he managed to stumble upon back in the 70’s while attempting to ascertain whether the Pan-Pacific Highway really existed.

The mezcal that won him “Best New Product” at Tales this year was the incomparable Ibérico Single village that is a riff on his “Pechuga” mezcal, produced in an ancient Moorish technique brought over by the Spanish where the mezcal is distilled three times with wild mountain fruits, almonds, white rice and a whole chicken breast.

Apparently one day, James Beard Award winning and El Bulli trained chef José Andrés showed up to Del Maguey’s distillery in Santa Catarina Minas in the state of Oaxaca with his research and development team, led by Chef Ruben García to taste Cooper’s Pechuga. They were obviously impressed, but suggested he try the technique with a leg of their prized Ibérico de Bellota ham, produced from free-range, acorn-fed specialty black-footed Ibérico pigs. Cooper took their advice and, again, the rest is history.

I had the opportunity to taste said mezcal at Cooper’s Ranchos de Taos studio recently, and was sent reeling with the heady quality of more flavors and umami pop I can remember tasting in any product, and probably won’t taste anytime soon. The entire Del Maguey line-up can be life-altering for some — there’s really nothing that comes close to it. Spirits aficionados will have to re-calibrate their bearings after experiencing Del Maguey. Their smoothness and complex palates send one into superlatives and their place among food seems an organic thing.

Greek philosopher Pythagoras claimed the true way to a person’s inner being was through the senses, and I would suggest this is particularly true for Del Maguey, but also for Cooper as well.

In a world where personal relationships are a thing to be taken advantage of to the end of the bottom line, Cooper inverts that viewpoint, placing the emphasis on heart-connection and the face-to-face. Take the relationship between he and Ken Price, the artist of Del Maguey bottle artwork. The two met in 1962, when Cooper was a neophyte artist just returning to the states from a year abroad studying in France.

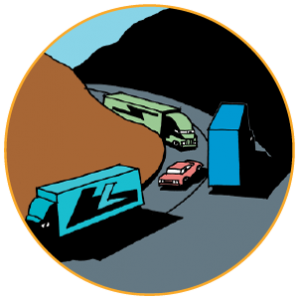

His next door neighbor was the older Price, who took the wide-eyed Cooper under his wing, taking him to culture palaces like the infamous Barney’s Beanery in Hollywood and introducing him to a circle of friends he still keeps. Price created the above round logo for the rare, wild mountain Tobala mezcal and Cooper feels it most signifies the Del Maguey mission, with the huge semi-trucks representing the “big guys,” the mass-producers, and the small, boxed in pink sedan as Del Maguey.

Although Price passed away in February of 2012, Cooper’s memorialized him on the website and pays homage to him with a recounting of his influence on Ron Cooper the man. I’ve oftentimes run across those who have a hard time accepting that a person can be at least two things at once. They can’t seem to fathom or accept that life can have parallel paths, that placing ourselves into boxes is the only way to “accomplish” anything. Is Ron Cooper a négociant of some of the world’s finest mezcals? Is he an award-winning artist with pieces in the permanent collection of the Guggenheim? How can he be both?

The question reminds me of the saying attributed to St. Francis of Assisi, “He who works with his hands is a laborer. He who works with his hands and his head is a craftsman. He who works with his hands, his head, and his heart is an artist.” Cooper fits all above categories and does so with a sense of humanity not known to many. Coincidentally, he does so about a mile down the road from the famous St. Francis of Assisi Church in Ranchos — go figure.