Every Hispanic community in the Southwestern United States has a centrally-located space that functions as a vehicle for aspiring and established local artists to display their work. This Casa de la Raza (house of the people) oftentimes doubles as a community center or space for a political debate . . . perhaps a polling place. If it’s happening in the community and pertains to the community, the walls of the Casa provide a forum.

This past Saturday, Taos may well have gotten its next Casa de la Raza in the form of local painter El Moisés’ Immaculate Heart gallery. The Mexican-born, Phoenix-raised artist christened his space with a daytime meet & greet with a local political candidate who provided free posole, biscochitos, and other goodies before launching the opening of his auspiciously-located art gallery.

Later that evening, the crowd was a cosmopolitan and smartly-dressed group of art lovers soaking up the images of an artist in complete control of his powers, and clearly poised to permanently add to the lush visual fabric of Taos.

I met Moisés several months earlier at the Harwood Museum’s Dia de los Muertos children’s celebration where he provided black and white copies of his images for kids to color.

Wearing his usual hat — not so much cowboy as Mardi Gras — blackout wraparound shades, and sporting an impeccably-coiffed handlebar moustache, he calmly sat amidst a throng of bustling kids coloring and cutting.

Behind the hat, shades, jewelry, moustache, and brightly colored costume, I recognized a man imbued with what the Japanese refer to as Hara — the quietly powerful energy that resides in the solar plexus of those attuned to the nourishing universal energy.

We’d gotten together a couple times since then and the more I found out about the flamboyantly-dressed yet soft-spoken artist, the more I realized my initial assessment was spot-on.

Father, Husband, feminist, philosopher, visionary… the variations of Moisés multiplied before me kaleidoscopically as December unraveled. Through the lens of his work I saw my own past in his timeless modernism rife with symbols of the radical Mexican-American Chicano movement.

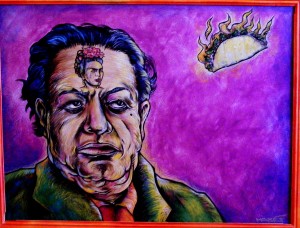

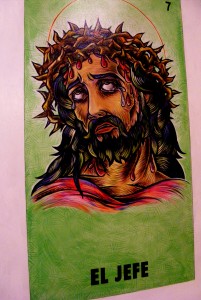

However, conspicuously missing from his work are the stalwarts of the twentieth century Chicano pantheon: the either/or feminist plight of the Madonna or the whore, the obvious machismo of the fierce warrior, and the stark violence of the crucifixion. In their place, he’s deftly incorporated the painting equivalent of Garcia Marquez’s literary magical realism, a visual fabric that transcends time and space, bringing the past, present and future together through the magic of the symbol — the language of mythology.

However, conspicuously missing from his work are the stalwarts of the twentieth century Chicano pantheon: the either/or feminist plight of the Madonna or the whore, the obvious machismo of the fierce warrior, and the stark violence of the crucifixion. In their place, he’s deftly incorporated the painting equivalent of Garcia Marquez’s literary magical realism, a visual fabric that transcends time and space, bringing the past, present and future together through the magic of the symbol — the language of mythology.

La Raza Cósmica and the Blessed Curse of Vision

In 1925, Mexican philosopher and politician José Vasconcelos developed the theory of la raza cosmica (the cosmic race) in reference to the new race of mixed-blood mestizos created by the coming together of European and Indian cultures. Said race was to be distinctly superior due to this miscegenation and would be able to transcend the Darwinist ideologies created to justify ethnic superiority by creating a future free from the “old world” and its destructive tendencies. According to Vasconcelos, this new fifth race would go forth into the world professing a new universal philosophy that would set the tone for a future characterized by an elevated sense of enlightened universal intelligence.

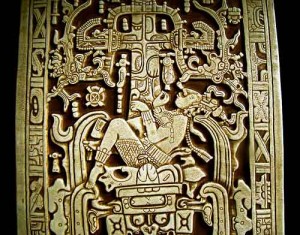

Whether an attempt to galvanize a repressed people or a reaction to Nordic notions of racial superiority, Vasconcelos’ cósmica theory seems prescient in light of the current interest in Mayan and pre-Columbian time-keeping regarding 2012, the end of the Mayan calendar, and the onset of the Aquarian age.

The paintings of El Moisés seem more like the blueprint for the symbols of the cosmic race and the corresponding Aquarian age than a continuation of Chicano nationalism. There’s a mystical quality to his work that deftly blends life and death, sacred and profane in a way that seems organic.

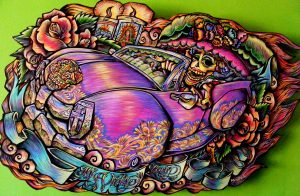

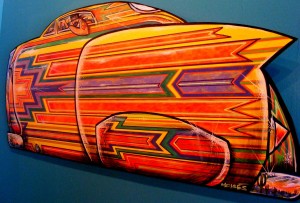

Alongside the skeletons and skulls of Mexican art, El Moisés adds a vibrant streak of color that seems more grateful dead than day of the dead. To a hardened vato in his low rider, he adds flourishes of yellow, purple and orange in a traditional Southwestern textile design, bringing together old and new technologies for the future.

Low Riders factor into his work as extensions of his subjects’ personas, grounding the image in a modern context, but borrowing from older themes. Recent works-in-progress feature images from the temple of Palenque, (AD 675-683) most notably from the sarcophagus of the temple’s builder Pakal and its iconography of an ancient spaceship, offering a connotation of time and inter-galactic travel which speaks volumes to the strange and splendid musings going on in the mind of the painter.

Low Riders factor into his work as extensions of his subjects’ personas, grounding the image in a modern context, but borrowing from older themes. Recent works-in-progress feature images from the temple of Palenque, (AD 675-683) most notably from the sarcophagus of the temple’s builder Pakal and its iconography of an ancient spaceship, offering a connotation of time and inter-galactic travel which speaks volumes to the strange and splendid musings going on in the mind of the painter.

According to Moisés, he started hustling his art as a precocious six year old, displaying a confidence that’s still evident in his strong, Impressionistic brush strokes and vivid life-affirming imagery. He paints what he loves and knows, following a theme in a subject’s life until he can transpose it to canvas. He calls the ability to lose himself in the subject’s world a blessed curse for subconsciously holding him captive, yet providing him with its potent symbol.

For inspiration he needn’t look any further than his own neighborhood and community, looking into that microcosm to find the universal themes that pique his interest. “There’s nothing new under the sun,” Moisés calmly said one recent afternoon as we idled in his gallery and he gently worked one of his hand-made and painted frames. Although the statement is Shakespeare’s, it seemed to fit Moisés’ serene manner perfectly.

All subjects, even those where death is the central theme, get the “Moisés treatment” in the form of a translucent, fluorescent wash. To most paintings he adds a dusting of glitter. The first time I noticed the effect I asked him what it was about, figuring it was homage to the days of Disco. Unperturbed by my question, he placidly responded it mirrors a technique employed by the Maya and Aztecs for creating glass mosaic. The technique could be seen as a metaphor for his life and work, a place where the fantastical and the mundane intermingle through the neon colors of the atomic age.

La Verdad

Online dictionary Wiktionary describes chingón as Mexican colloquial for:1) someone who’s very intelligent and can do things quickly 2) someone who likes to mess with people 3) someone or something that is cool, awesome and very good.

El Moisés personifies all three definitions and goes beyond by exhibiting barrio wisdom as well as a global consciousness that carefully chooses from the well of timeless images with assurance, incorporating them into an oftentimes fantastical tableau punctuated by his sly humor. He transcends the role of the artist as the enfant terrible by his steadfast dedication to his role as father and husband. Unlike the late, great Jean-Michel Basquiat, who constantly was being evaluated in the press for being either a great painter, or a great black painter, El Moisés needn’t worry about such dilemmas.

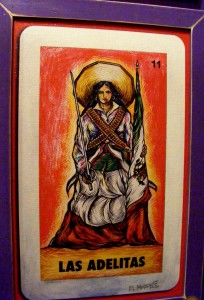

He is Chicano and proudly displays that fact. Aside from being Mexican American, one must subscribe to a specific political ideology and way of seeing the world to accept the title “Chicano.” From 1965-1975 Radical Chicano politics were at the fore of national press images. Cesar Chavez and his banner of the Virgen de Guadalupe and iconic black eagle were the movement’s symbols and they were up and down the streets picketing, arguing, eating, laughing . . . it was a heady time, full of the sort of substance not seen or felt in America since: hope.

As Emilio Estevez tells us in his 2006 film Bobby, that particular substance was extinguished one fateful night in 1968 in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel. Across town in the former barrios of Chavez Ravine, now home to the Dodgers, Don Drysdale pitched his sixth straight shutout and was probably celebrating in the locker room when Bobby Kennedy took a few bullets in the kitchen of the Ambassador. Upon his death on July 3rd, 1993 in a hotel room in Montreal, there was found among Drysdale’s personal items a cassette tape of Kennedy’s victory speech that night where he announces his feat to a cheering crowd moments before that gruesome point in time. The contents of that tape will forever be that moment when the wind was completely sucked out of the sails.

After experiencing the loss of that sort of hope, it’s difficult to look at the current brand of HOPE and see any meat on its bones. When perusing the art of Moisés I feel a twinge of that old hope resurfacing. His art is specific, yet not exclusive, and it’s codifying the 21st century meaning of Chicanismo in its most accessible form.

After experiencing the loss of that sort of hope, it’s difficult to look at the current brand of HOPE and see any meat on its bones. When perusing the art of Moisés I feel a twinge of that old hope resurfacing. His art is specific, yet not exclusive, and it’s codifying the 21st century meaning of Chicanismo in its most accessible form.

Every age has its symbols, and, oftentimes, it’s the symbols that survive the civilization. By utilizing timeless themes specifically, Moisés has managed to capture the ethos of our time from his own particular lens. He’s also managed to elevate the meaning of the symbol to its former, loftier position, restoring it to what author Luis Leal describes in his 1989 essay In Search Of Aztlan as “The significance of the spiritual. The image that we see reveals to us or makes us aware of the existence of something beyond the material. In other words, the sensory image, or symbol, is associated with a concept or an emotion.”

Something tells me if future civilizations get the opportunity to discover our time and this place, among the tools they’ll use to glean significance will be the art of Moisés.