Autumn is here and Earth’s gravitational forces turn in on themselves as the nights grow longer, the days shorter. In the plant world, roots are developing intricate underground networks, diving deeper into their source of nutrition. Energy across the northern hemisphere is brought down a notch as we head toward the nadir of the Winter Equinox.

It’s a time for introspection, for re-charging our batteries before we head out of the darkness into the light of Spring, and the cycle begins anew. In this time of quiet introspection lie the seeds of change and interpersonal growth. Somewhere in the darkest nether-regions of Fall and Winter, we seek the light of knowledge and love.

Our emotional life is in as much need of re-charging as our physical bodies, and to that end, the holiday season is about re-connecting with those who are pertinent in our lives, as we seek beauty and love to keep our inner fire burning.

Halloween and El Dia de los Muertos are the gateway to this cycle, as I was subtly reminded this past weekend while perusing the expansive rooms of the Harwood Museum. Within the hushed solitude of its walls it was easy to reflect on life past, present, and future, as images leapt out to pique particularly relevant thoughts or memories.

Museums are receptacles of memory — thus the onus is on the Curators to determine what memories are displayed, and how so. Here in the American Southwest, there are ample amounts of indigenous as well as modern art to choose from, so much so that it boggles the mind with possibilities. From pottery and jewelry, to murals and wood carvings; retablos and rugs, paintings and photography . . . so many choices and periods to focus on . . . and so little space.

Luckily, for us Taoseños and our visitors, there are a variety of spaces to view the artistic endeavors of those who’ve come before us, as well as our contemporaries. Some are quaint, and rife with arcane pieces whose appeal and relevance to the local fabric are undeniable, á la the Millicent Rogers Museum. Some are reminiscent of the Bohemian vision of the Shangri-La of Taos, a place ripe with magic and possibility; and some meld the best of both these worlds with other timeless elements, in an unique manner that undeniably speak of this place.

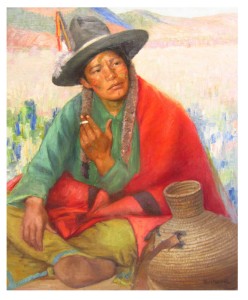

From the indigenous perspective, “artwork” takes on different implications from European interpretations, in the regard it generally serves a utilitarian function, as well as being layered with spiritual themes that speak of a way of seeing time as cyclical, rather than linear.

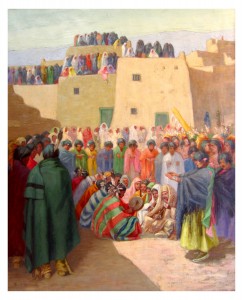

The 1920’s and later bohemian landscapes and portraits serve more of an anthropological function, as they seek to record particular individuals and places in all their vividness. Both styles have been elegantly fused in the case of the Harwood and Millicent Rogers spaces, and as residents it’s our duty to go and pay homage to our region’s storied past, so we might better understand the present, hopefully thinking collectively for the future.

From Tenochtitlan to Taos: Los Tres Grandes and Art for the People

“The legend of Aztlan never died; it was only dormant in the collective unconscious. For people of Mexican descent, Aztlán exists at the level of symbol and archetype. It is a symbol which speaks of origins and ancestors, and it is a symbol of what we imagine ourselves to be. It embodies a human perspective of time and place.”

— Rudolfo Anaya, Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland

The Mexican Mural Movement that flowered under the 1920-24 presidency of Mexican President Álvaro Obregón was spearheaded by a trio of Artists who would come to be known as Los Tres Grandes: Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. The trio had far reaching implications into the development of contemporary American art, spawning several movements and securing a place for public art in traditionally non-accessible areas.

The Mural movement of the 1970’s was one such movement, and its ensuing assimilation into modern pop art has provided us with some of its most enduring icons; the skulls and skeletons of periodical publisher and artist/printer Jorge Posada; the cubist elements of Aztec and Mayan monoliths; the images of the indigenous peasantry of ancient America, from Mexico City to Taos; from the Pacific to the Rockies . . . the elements the trio sought to incorporate into their artwork worked so well in the genre because they’re ingrained in the landscape, and local indigenous culture has maintained the connection to that landscape and its mythic past.

The 2001 LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) exhibit, The Road to Aztlan: Art from a Mythic Homeland, afforded one the opportunity to chronologically walk through the artistic history of the land of Los Tres Grandes up to the present. From Aztec Codices, to Retablos, from photography and prints to jewelry and baskets, the exhibit was impressive in its scope and range. The main impression taken from the show was that the current borders imposed on El Camino Real (from Mexico City to Taos) are temporary and random.

The historical elements of the show stripped away said borders before one’s eyes, the forensic evidence too plentiful and captivating to deny the fact the Mythic land of Aztlán is vividly alive in the collective unconscious of those open to it.

The Chicano movement that emerged in the late 1960’s was nourished by, and in turn produced images and symbols of the artistic lineage it was borne of. The movement was, and is, an attempt by the mixed-race populace of America to make sense of an assimilation pattern that began shortly after European contact and continues to the present.

The elements employed by Los Tres Grandes form the bedrock of the Chicano movement’s artistic endeavors, using religious iconography and vivid color to express images of self-ridicule and aggrandizement — the coping mechanisms of “la raza” (the lower classes who have a strong connection to their indigenous roots).

This past El Dia de los Muertos, the Harwood featured the artwork of El Moisés as part of their events for children. I found the flamboyantly-clothed El Moisés calmly sitting at a table with a host of children around him, nonchalantly coloring images of his artwork. The room was bustling with parents and kids milling about, with a few of the parents giving El Moisés’ outfit a double take. Perhaps it was the silver nail polish, or the brilliantly plumed cowboy hat on his head, but it was evident by his attire that the man is an artist.

The website for El Moisés proudly proclaims that he is “The voice of the contemporary Hispanic art movement,” and I wouldn’t argue with that statement. His images contain elements of the best of the muralists, while deftly incorporating a sensitivity and intelligence that works perfectly in pieces like “Friday Night Ritual,” a multi-colored, cubist influenced image of a Vato coolly ironing his outfit for the evening’s impending cruise. The warm colors and graceful form of the Vato lend a sense of pathos to the image, imbuing the hardened and heavily-tattooed subject with an element of gracefulness. In the background a can of “Magic Sizing” starch sits among the traditional religious duo of the Hispanic pantheon: the Virgin Mary and Jesus, lending a comic element to the mundane aspects of everyday life.

The cornerstone of the Mexican Muralists vision was art for the masses. To that end, the Murals became the calling card for the trio. Public art was meant to be a galvanizing element in the community, a way for the populace to reflect on their mutual past and collective future.

Here in Taos, the Harwood has made concerted efforts to incorporate public art into their space. Recently, they incorporated local duo Promo Hobo, who’ve raised the bar in the area for informative and conscious public art, most notably through their mobile mural “Restore the Rio Pueblo,” which brings attention to the environmental tragedy of the local Rio Pueblo that flows from Taos Pueblo’s Blue Lake through the Pueblo and town of Taos, before converging with the Rio Grande south of town.

If the museum is the receptacle of memory, it needs observers to view its contents. With free community days available through both the Harwood and Millicent Rogers, there’s no excuse to not take the time to go and reflect on the symbols of this place.

Through their perspective, we are meant to examine our place in our time — with the beauty of the well-worked art object as the muse for inspiration, and the quiet, reflective expansiveness of the Museum as a meditation-hall environment.

This Fall and Winter, take some time to unplug yourself and submerge your thoughts into the collective unconscious via the artifacts of those who’ve walked the path before us. The inspiration gleaned from doing so will prove fruitful to one’s sense of self.