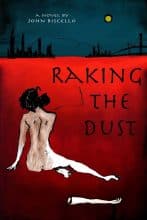

It’s 11:30 in the morning on Easter Sunday and I’m fast approaching deadline — the only way I seem able to work. I’ve lost my leather clad journal containing the notes for this interview somewhere in the chaos of my office, a maelstrom of books, scraps of paper with incoherent rantings scribbled upon them, bicycle and motorcycle parts along with the detritus of ski season mixed freely with freshly washed but unfolded (and likely to remain so) laundry. I have a dozen reasons not to write; the garden needs attention. The dishes need washing. It’s too nice outside. It’s a struggle anyone who has ever sat down to put words to page will be familiar with; the resistance inherent to the creative process. For John Biscello, this is anathema. With three published books and a recently completed fourth, along with multiple play writing and performance credits, he may well be Taos’ own version of musician James Taylor, “The hardest working man in show business.” His most recently published novel “Raking The Dust” is a thinly veiled autobiographical romp through a town that reads suspiciously like a dark version of Taos. So the sun is shining. My bike needs riding. I know what John would tell me. “If you want to be a writer, write”. We’re just going to have to wing it on this one. Here we go.

CM: Being born and raised in Brooklyn appears to have had an influence on your writing…

JB: Definitely. Just the other day, I was thinking about hanging out on the street corner, hanging out in front of the train station — we’d all hang out there and there was this riotous energy, almost this social club of our neighborhood, being either at the park or the train station, drinking, smoking all that. But the level of the firecracker dialogue, the level of, you know, brutal sarcasm, helped thicken my skin. And I was like pretty much middle of the pack, as far as being able to dish it out, but there were some who you just couldn’t touch, there were like the Dons of sarcasm, they were just so witty and quick and they would have no problem going for the throat. Some people had almost it felt like, no conscious or compunction. Anyway, I was thinking how in regards to me, in some ways that became a component of my storytelling — dialogue, especially dialogue and developing an ear. Like a lot of witticisms and put downs, really fast and quick you know, or just puns and verbage. And then coupled with that, I had my own private world, my nerdy part of being in books and reading and I think at some point the two began to sort of meld together.

CM: So when did you start writing?

JB: Oh man, when I was a kid, like pretty young. Because I was so into comic books and detective stories. Do you remember how at the end of comics, there’d be a preview of what was going to happen next issue? Like cliffhangers? I remember writing serialized stories about the Red Falcon, who was my hero when I was young. I’d write these stories, and I’d imagine that I had a huge audience and that they were all waiting for the next issue to come out. Jack Booker was my detective series.

CM: Brooklynites of your era are notoriously “homebound.” What caused you to leave the neighborhood?

JB: I feel like what really opened up my world was when I started going into the city [New York] for an editorial internship I had at a parenting magazine. It’s a funny thing about where I grew up, even though the city is right there, it seemed far and scary to us. We had our neighborhood. It was its own place. We didn’t go over the bridge, I didn’t take the train a lot. So it was this faraway land, even though in reality it’s only like 20-40 minutes away. So when I began to work in the city, suddenly I was exposed to all these different types of people and ideas. My neighborhood, as is true of many neighborhoods in Brooklyn, it’s almost like an enclave of singular thinking. I also really liked when I began to travel, [I] liked coming back home. I always felt a little like Kerouac, because even though I’m out having these great adventures, I always came home, to Mom and Grandma and the place I grew up in.

CM: Kerouac’s a hero of yours, isn’t he?

JB: Yeah, he was a big influence, definitely. Other than school, I didn’t have much of a literary education. So when I first discovered Kerouac, at age 18, and it was the same with Bukowski, I go into work and I’m telling people “Hey, I don’t know if you’ve heard of this guy, Jack Kerouac, but he’s amazing!” And they’re looking at me, like “Yeah, we’ve heard of him.” It sounds funny, but up until that point, other than what we were assigned to read in school, I was mostly into true crime, horror, serial killer type stuff. I used to think that if I wasn’t a writer, I’d be a killer, because I didn’t know what to do with all of my anger and rage.

So anyway, when I discovered Kerouac, I thought — here’s a whole other way of telling a story. Because of the verve and the intensity and obviously there’s the whole spirit of… I think what’s so great is, forget about all the drugs and the sex, all that aside, I think what will never go out of style for him is just the exuberance and the spirit of boyhood.

CM: Right, there’s very much a sense of innocence. There’s some of that in “Raking the Dust”, where even though Alex is this kind of condemnable character, he’s also childlike enough that we end up forgiving him.

CM: Right, there’s very much a sense of innocence. There’s some of that in “Raking the Dust”, where even though Alex is this kind of condemnable character, he’s also childlike enough that we end up forgiving him.

JB: I wrote “Raking the Dust” in the process of getting sober, which actually changed a lot of the revision and the last third of the book. The original ending, I feel, was much darker and more enigmatic. It actually ended with Alex looking in the mirror and watching himself disappear, piece by piece.

CM: Do you feel that getting sober has changed your writing?

JB: (After a long pause) Absolutely. Although even when I was drinking, I was always very disciplined and I’ve never been one to drink and write at the same time. I always wanted to honor the process, have always had a great reverence for it. Also one of my greatest fears has always been that I might squander something, wake up one day and see that I’d ruined myself. And yet, I wanted to be able to ruin myself and write, to keep both things in my life.

CM: You’re not only a novelist, you’re a playwright, a teacher, a cinemaphile. Do you feel more aligned with one of those things than another, or do you feel that they all kind of weave together?

JB: I would say at this point in my life that movies have as much influence on my life as literature, if not more, especially in the last year or so. I go into phases where I’ll study different directors or styles. I kind of set it up that way, like a curriculum. And so I’m watching how they frame shots, or the lighting or themes that are repeated, like that’s the beauty for me — when someone has a vision, and it’s like that vision extends beyond a single film, like David Lynch. Actually, what I’m working on now, [Nocturne Variations], is so heavily influenced by cinema, thinking in terms of shots and framework. I love this idea of blending so many different forms, almost a collage of styles.

CM: How important is it for you, as a writer, to be a reader?

JB: I feel like it’s not possible to be one without the other. Maybe it was Ginsberg? Who said that you should read three or five times as much as you write. I didn’t go to college. I took writing courses, but I feel like not having that continual frame of reference would be limiting.

CM: Can you speak a little to the literary scene of Taos, as an artists community?

JB: There’s such an influx of new ideas — The Paseo, Taos Shortz, Misfits, Malcontents and Mystics. I feel, more than being specifically literary that Taos is a hub of creativity and that hasn’t changed. I really dig this contrast of the cosmopolitan blending with this ancient, rustic vibe.