“Sometimes it’s just the trick of saying you are one thing when others say you are something else. When people want to say something is a windmill but you know perfectly well it is a giant, who is to say otherwise?”

– Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

Melinda Bateman of Morning Star Farm in the hamlet of Arroyo Seco made further strides in her quest to bring Biodynamics to Northern New Mexico this past April 12th and 13th, when she held a two-day workshop at Farmhouse Cafe & Bakery in El Prado.

A consistent contributor to the produce supply of Farmhouse and other high-end restaurants, Bateman is a long-time Biodynamic practitioner who recently attended Biodynamic stalwart and Homeodynamic innovator Enzo Nastati‘s rare American seminar in Paonia, Colorado.

There were concerns at the outset for Bateman, who wasn’t quite sure how she would convey the entirety of what Steiner’s Biodynamic vision was to a group. It’s a valid concern; particularly with those that have just been introduced to the concept, or may have come across negative comments beforehand and therefore have preconceptions.

In the end, she wound up relying on her personal experience and proceeded from there, mixing personal anecdote with comparisons in her recent Nastati seminar with traditional Biodynamic teachings, giving all viewpoints to the students.

Day one of the workshop started with an hour long introduction to the Biodynamic system, where Bateman used a chalkboard to draw out concepts. In particular, she described how Biodynamic preparation #500 works and is prepared, as that was the first Biodynamic activity of the workshop.

“We’re combining an animal product, with a mineral product, with a human performing an action we wouldn’t commonly do,” she calmly explained, as the sound of kitchen chatter and pots and pans clanking emerged from an adjacent, open window of the Farmhouse kitchen, and the occasional curious passer-by momentarily lingered.

“And then we’re going to bury this in the earth to absorb its energy…something else I’d like to point out that factors into the 500 — and in fact all of the preparations…that if you think about the winter months, that’s when the earth is most earthly. All this vegetative matter that has burst forth in the spring, in winter essentially goes back into the earth.”

“So the earth is more herself at that time of year,” Bateman adds, now standing with her arms outstretched as attendees quickly jot notes and white, puffy clouds start to stack up against Pueblo Peak in a stiffening breeze.

She goes on to discuss how the cow’s complex digestive system, comprised of four stomachs, vitalizes the grasses it feeds on and is the primary source for the preparation. She adds that the horns and hooves of the cow both act like mirrors for retaining the interior life forces of the cow, but it’s the horns that connect it to the sun and the solar force of ascension, using her long hands to make the curve of a horn pointing upwards as she finishes her sentence.

The dung of a lactating cow is to be used for the preparation and packed into cow horns and buried for about six months before being dug up; the resulting matter being dry and dirt-like, looking nowhere near the green mess initially packed in.

That’s taken and portioned out into small units to be dynamised in water via an hour-long stirring, preferably with the hand, creating a vortex by going alternately clockwise and counter-clockwise.

Bateman has everyone huddle around as she sits over a bucket of two-and-a-half-gallons of water to demonstrate the technique, sticking her right hand in and stirring vigorously while saying, “I’m going to pull toward my heart…and you can see how this is making this big vortex.”

“And then I’m going to stick my left hand in and also pull toward my heart…and this creates this level of chaos where you’ve got two opposing vortexes going on. And you can think about it as sheets of water molecules going past one another,” she adds, intently bent over her bucket as the clouds part as if on cue and the water shines and sparkles in the momentary sun.

“Scientifically, that’s why Biodynamic works so well with this type of stirring — because you infuse every molecule with whatever force you want it to carry. I think it’s some sort of occult science…something we can’t really see…”

“Magic!” an attendee calls out.

“Yeah… you can call it magic if you want,” Bateman cavalierly replies, “But Steiner would want you to call it science.”

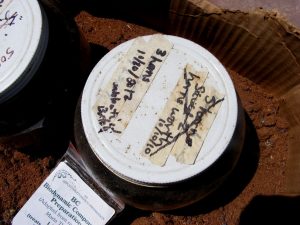

A few minutes later she’s portioning off water from her well in Arroyo Seco to individual buckets for attendees to stir in their small amounts of preparation #500 that have been pre-aged by Bateman, as well as some procured from the Josephine Porter Institute in Virginia, who’ve been producing Biodynamic preparations for close to thirty years.

A few minutes later she’s portioning off water from her well in Arroyo Seco to individual buckets for attendees to stir in their small amounts of preparation #500 that have been pre-aged by Bateman, as well as some procured from the Josephine Porter Institute in Virginia, who’ve been producing Biodynamic preparations for close to thirty years.

Stirring can be a taxing exercise, but can also prove meditative, affording the ability to lose oneself in the rhythm, process, sound and feel of water gently swooshing.

When Steiner introduced Biodynamics in the 1920’s, he was clear the state of mind of the stirrer and stirring with the hand (as opposed to a stick, or machine) played a part in the efficacy of the treatment, emphasizing it operated in the same unseen realm of energy that all Biodynamic treatments work, mirroring what quantum physics originator and 1918 Nobel Prize winner Max Planck said in his acceptance speech, specifically that, “Matter as such does not exist; all matter originates, and exists, solely by virtue of a force which induces particles to vibrate.”

After the stirring, everyone convenes at the Farmhouse plot at the base of Pueblo Peak as the wind now steadily comes from the northeast and sheets of snow lazily drift behind the rounded shoulder of El Salto ridge. Attendees take turns walking the rows, dispersing the tea of #500 and water by hand, lightly dousing the ground as they pass with gentle sweeping motions. After half-hour, or so, Bateman stands encircled by all attendees as they call it a day and make plans for tomorrow’s compost-pile building as the inevitable snow and rain begin to close in.

When the (Buffalo) Chips Are Down

Overnight rain gave way to a sunny, if windy morning that found most attendees bundled up with a warm beverage as Melinda knelt at her chalkboard and drew some diagrams while light chatter filled the air and the Sunday morning breakfast crowd started to straggle into the parking lot.

Overnight rain gave way to a sunny, if windy morning that found most attendees bundled up with a warm beverage as Melinda knelt at her chalkboard and drew some diagrams while light chatter filled the air and the Sunday morning breakfast crowd started to straggle into the parking lot.

Melinda fielded some questions as she drew out the day’s concepts, taking the time to make sure that her answers were fully understood before taking another.

And so the morning passed, leisurely and without incident as weather crept up from behind the mountain, and before we knew it, it was time for lunch followed by the compost-pile building.

Melinda’s truck was parked in the back field packed to the top with dung to mix into the pile, and while she and I walked out to grab some shovels I asked her where she got such a copious amount.

“From my neighbor,” she calmly replied. “Its buffalo, mostly, mixed in with a little horse…and of course some straw,” she added as we were now standing at the tailgate looking directly at it.

“Buffalo,” I say back to her, more as a question.

“Yeah, the Paonia Biodynamic group has been working with it, and they’re very excited about the results.”

“Huh,” I grunt, momentarily at a loss for words. “Yeah,” she enthusiastically adds, “Think about it…cows were used in Europe because they’re indigenous there…Buffalo is the North American animal. They have horns too, and the Paonia group has even made #500 out of some them.”

“Really,” I enthusiastically blurt, now very excited.

“It’s an exciting time for American Biodynamics,” she adds over her shoulder as she climbs up into the truck and grabs the shovels as I break out my camera. She quickly hops back out and heads over to the site where the compost pile is to be built, leaving me to ruminate on the Buffalo compost and preparation #500.

Steiner considered his 1928 series of lectures that eventually became Biodynamics somewhat incomplete.

While he knew the techniques worked, he hadn’t really codified the system as his health was quickly declining and he knew he wouldn’t be able to finish, so he told his followers they would have to do the job, knowing full well they would face ridicule from particular quarters.

Accordingly, he wanted them to take their time and make sure the system was beyond reproach when eventually presented to the world.

History would prove he was correct in doing so, as Biodynamics remains on the fringes of society — where it’s pretty much been since Steiner put forth his original lecture, “Spiritual Foundations for the Renewal of Agriculture.”

It’s been the spiritual component people have had a problem with, combined with the perceived lack of empirical data in support of its efficacy.

But in these “spiritual” times where a good deal of people are searching for tangible results for something of deep meaning, Biodynamics is getting a well-deserved second look, with select Whole Foods stores recently displaying specific Biodynamic sections and the Biodynamic Farming & Gardening Association’s numbers rapidly on the rise.

Empirical data continues to be recorded with many comparative studies between conventional farming, Organics, and Biodynamics being done, many of which can be found on the Demeter (the regulating arm of Biodynamics) web site, as well as the Farming & Gardening Association’s.

What do the studies find? Primarily, that there’s not really a lot of difference in Biodynamic vs. Organic, but there are, in most cases, marked differences in the two versus conventional farming.

What Biodynamics does do is consistently give a healthier supply of what’s being grown, as well as a marked qualitative difference that at the end of the day is really unquantifiable.

However, most people find Biodynamic fare more flavorful, more itself.

The compost pile is at the heart of Biodynamics and any Biodynamic farm, creating controlled environments where microbial activity occurs quicker than it can in soil, creating humus.

The compost pile is at the heart of Biodynamics and any Biodynamic farm, creating controlled environments where microbial activity occurs quicker than it can in soil, creating humus.

The six Biodynamic preparations placed into the compost pile are as follows: 502, Yarrow flowers stuffed into a stag’s bladder, hung in the sun over summer and buried in autumn until spring; 503, chamomile flowers in fresh cow intestines made into sausages and buried in a terra cotta flower pot in autumn until spring; 504, dried stinging nettle picked in summer and buried in autumn in an unglazed earthenware pot, left for a year, run through a sieve upon being dug up; 505, chopped oak bark placed in a sheep, goat, or cow skull and buried from autumn till spring in a damp area then dried in a glass jar; 506, dandelion in animal casing (mesentery), buried in autumn during descending moon phase and lifted in spring; and 507, valerian flowers ground in a mortar & pestle, diluted 1:4 in rain water, placed in a loose-lidded glass jar, and left in the sun for a week, then strained into a bucket of rainwater, dynamised, and sprinkled on top of compost heap.

The preparations work in conjunction with the phases of the moon and — here’s where Biodynamics differs from any other type of farming — also with the so-called “inner” planets of our solar system (Mercury, Saturn, Venus, Mars and Jupiter), harnessing their energy via the preps and the compost pile.

Back at the Farmhouse spread, Melinda and her crew are hard at work getting the pile built. The first layer is garden trash: sunflower stalks, stems, things that won’t decompose quickly and allow aeration, followed by a layer of nitrogenous material, in this instance, the buffalo dung, mixed in with carbon in the form of straw and leaves, followed by the compost preparations.

Due to the elevation and the ample sunlight New Mexico receives, Bateman waters copiously to ensure the pile doesn’t dry out. In about an hour it’s time to put the preps in, and she brings out her box made specifically to hold them — made of local red fir and stored in a small walk-in refrigerator.

She places the preps in by hand as attendees continue to place shovelfuls of compost over, and in no time it’s done. Afterwards, all gathered in Farmhouse for a snack and to go over the preparations in depth.

Later that night on my way into town I pass the compost pile as a light snow began to fall, which I took as a beneficial omen. It gave me cause to reflect on this, the only biodynamic compost pile in Taos, as it sat stoically at the foot of Pueblo Peak, composed of Buffalo dung and brimming with the hope that animal and land might be joined again in the future for the benefit of all its inhabitants.

Call it science; call it magic, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that after over a century of neglect, America has begun to heal herself.